Opening with a shot of ice cracking in the shape of a bat symbol, Nolan’s latest film starts with a metaphor it returns to time and again: that of the dangerous waters below consuming those who fall into them. The device in use here is the literary association between water and the subconscious, a technique also used in Nolan’s masterpiece Inception, where limbo was located “on the shores of our subconscious” and in which water imagery grew more intense and violent the further its characters travelled within themselves. Yet whereas Inception used water symbolism in the service of religious allegory, in the Batman trilogy Nolan uses it to make a political critique of the American War on Terror.

This is the reason for the symbol’s association with Batman, a figure who rejects democratic processes in order to fight terror with terror. A “dark knight” who lives in a cave dominated by a waterfall (“water” + “fall”), Batman is the embodiment of Bruce Wayne’s aggressive inner-psyche. The script jokes about this in many ways, such as in one scene where Batman (Wayne’s “real” identity) attends a costume ball dressed up as his alter-ego. But whether made through levity, or more subtly as in the scene where John Blake intuits Bruce Wayne’s real identity by virtue of their shared thematic identity (St. Swithin is the patron saint of rain), the thematic point is that Bruce Wayne is the “mask” worn by Batman just as Wayne Manor is the “mask” which covers the dark caverns below. As with the rivers which run through subterranean Gotham or the dark waters under the crust of ice, the evils in this film all lurk within and below.

This symbolism makes Batman a profoundly negative figure (the hero the corrupt city “deserves” but “not the one it needs”), and explains the otherwise baffling connections Nolan draws between Batman and the ostensible villains he fights. As an example, consider the way Batman Begins introduced the Scarecrow character to comment on Bruce Wayne’s own inner fears, giving the villain a plan to transform Gotham’s water supply system into a dispersal mechanism for exactly the sort of fear-induced violence that the film associates with Batman’s water-drenched subconscious, or the way the second film featured a villain whose criminal theatricality echoed most closely that of Batman himself.

This mirroring between Batman and his opponents continues in The Dark Knight Rises. A former member of the League of Shadows, Bane is like Batman a “masked man” who embraces vigilantism in response to past suffering. From the very opening scene our new villain spouts morally suspect dialogue which applies equally to both characters (“nobody cared who I was until I put on the mask”), while the script emphasizes the connection even further by giving both the same love interest, dehumanized mechanical voices, and by surrounding each with imagery of caves and water and darkness and fear. The “batcave” below Wayne Manor is even mirrored by Bane’s construction of a similar lair below Wayne Enterprises, the parallels holding down to the shared waterfalls and digital surveillance systems.

In previous films Nolan hinted at the negative nature of Batman’s vigilante crusade: note the destruction of the (heavenly) garden at the end of the first film, or the transformation of Batman into a hunted criminal at the climax of the second. Yet Nolan is never so overt in his condemnation of Wayne as in this final installment, which shows how Bruce Wayne’s vigilante behavior has led on a personal level to his shattered health and bankruptcy, and on a political level to Gotham’s decay into a grossly iniquitous surveillance state (it is hardly accidental that the tools first used by Batman have by now become instruments of state surveillance). Thematically, Nolan is showing us how Bruce Wayne’s personal desire for retribution and revenge is mirrored in the growing corruption of the civic authorities and the entrapment of Wayne Enterprises (the “heart” of the city) in criminal capitalist webs. Individual corruption is mirrored by social decay. And this is the point it seems to me basically every critic has missed. For while critics seem to wish to pick sides, Christopher Nolan is not telling us to cheer for the “boys in blue” any more than he wants us to side with Bane’s orange revolution: the battle between the two is rather compared to the football match which figuratively kicks off the revolution (“let the games begin”), and to which Batman returns to get “back in the game.” Who wins is irrelevant to what actually matters: the fate of the spectators.

Broadly understood, what The Dark Knight Rises argues is that the War on Terror has turned into a destructive force which is undermining democracy and prosperity. Thus the film’s multiple references to A Tale of Two Cities, which depict Gotham as an unjust society similar to the ancien régime which preceded the French Revolution: a place where political “structures” have become “shackles” on its citizenry, permitting the rich to gorge themselves while the poor go hungry. Economic corruption has become inseparable from daily life. The stock market has transfomrmed into a “two-faced” game designed to “steal” from the masses, while “the rich don’t even go broke like the rest of us,” as Selina Kyle laments to Bruce Wayne. Corporations which formerly showed concern about their public image are even openly criminal themselves, relying on mercenaries to secure lucrative “mining” contracts (and note the subterranean imagery suggestive of the expanding corruption of the city itself).

Far from representing any morally defensible system of law and order, the government in this society has devolved into a perversion of justice, or a metastasized embodiment of Batman’s subconscious values. For what does the opening aerial sequence depict if not an act of vigilantism by the state itself? We see here two prisoners threatened with death in a process that — in parallel to the revolutionary courts to come — offers the defendants “no lawyers [and] no due process.” The nighttime visuals of Gotham which follow further emphasize the city’s status as a fallen dystopia in which a corrupt elite governs the masses using the same tools of “theatricality and deception” (read: lying on television) embraced by the villains in the saga. And Nolan’s implicit critique of Batman and Commissioner Gordon’s conspiracy at the close of the last film is now made explicit in a deliberate edit which superimposes the face of the “two-faced” villain over the police commissioner’s own as the latter goes on television to defend a law which he knows to be “based on a lie” and whose “teeth” are used to imprison the innocent.

In sharp contrast to the city we are told was uplifted out of economic depression by the progressive and unfearful behavior of Thomas Wayne in ages past (the healing doctor whose symbolic legacy was explosively destroyed in the second film), Gotham has devolved under the counter-example of his son into a two-tiered society run by an elite financial class in which the poor are criminalized simply for trying to support themselves. If the twin ferry sequence in the The Dark Knight showed Gotham’s citizenry acting with less moral authority than than its prisoners, in this film we see criminality become commonplace, as the script emphasizes that crime is a matter of survival rather than conscious choice, something as evident from Selina Kyle’s remark that “a girl’s gotta eat” as in Bruce Wayne’s suggestion that perhaps she is “saving for retirement.” Likewise, without support from charities, the only jobs for children are both literally and figuratively in the water-drenched sewers of the city. Crime has become a way of life, while mass surveillance tools like fingerprint and face-recognition technologies have become ubiquitous methods of social control. And nor is there any possibility of escape, when Bruce Wayne tracks down Selina Kyle using nothing more than “public databases” and urges her to “start afresh” noting that the ground (read: ice) is “shrinking beneath her feet,” Kyle is right to mock his naiveté. And when she tells him it is not possible to escape she is proven correct: Selina’s only attempt to flee is foiled by the police, whose dossier on her stretches back to early adolescence and who arrest her for a crime (kidnapping) of which the script suggests she is entirely innocent.

Seen in the context of Nolan’s trilogy as a whole, which starts with a biblical loss of innocent in Bruce’s fall from the garden (a moral failure that follows the children’s unearthing of a symbol of violence and his subsequent theft of it) and descends stepwise from there into authoritarian dystopia, The Dark Knight Rises makes it hard to imagine how any reasonable critic could argue that Nolan is defending Gotham society. And how could anyone seriously attuned to what Nolan is doing cinematically fail to notice the way his script parallels even the most perverse injustices of the revolutionary system in the excesses of pre-revolutionary Gotham? When Bane claims he is acting as a “necessary evil” to cleanse Gotham of an oppressive government and return it to the people, we are not meant to take his pronouncements at face value (his goal is the destruction not reform of the city). But his criticism of the status quo is meant to stick even if his own methods are as theatrical and deceptive as those he opposes. Neither his revolution nor the society he attacks provides due process or justice to its citizens, something symbolized and criticized in the way criminal sentencing is handled in both societies by the exact same person.

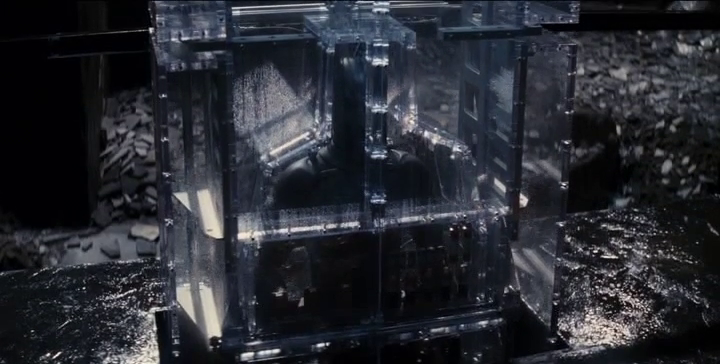

The prevalence of American iconography in Gotham (particularly in the national anthem, football game, and the repeated visuals of increasingly tattered flags) suggests that the Nolan brothers are indeed commenting on contemporary America and its extrajudicial War on Terror. But their approach is also less political than allegorical. For they do not intend us to see Batman as a noble figure defending an embattered establishment so much as a symbolic agent who illustrates the cause of its decay through his misguided embrace of anger and fear, and his refusal to trust the judgment of others as is required in any democratic society. So this is the reason we see here a reference to Fritz Lang and there a shot from Sergei Eisenstein as the populist uprising is cinematically compared to both the workers’ uprising in Metropolis as well as the 1917 revolution which destroyed the Tsarist autocracy. And then we see Dickens and the French Revolution in a montage which shows us the storming of the Bastille, the persecution of the rich, and the creation of unjust kangaroo courts, as the surface of the city cracks open like ice on a frozen lake, and Gotham’s subterranean violence is unleashed upon the city with images of snow and the coming of winter.

Yet if neither the revolution nor the political establishment is earnestly deserving of our sympathy, there is one more question left to address: how should we interpret the ending of the film and what if anything is the moral message of Nolan’s entire drama?

In traditional mythological storytelling, we see the renewal of society when the hero redeems himself, casting off his destructive inner traits or beliefs which are allegorically reflected as the evils of the outside world. This is the reason the script insists that the problems in Gotham can only be fixed from “inside the city,” a reading that suggests we treat Bruce Wayne’s escape from the pit as a symbolic rebirth. And there is certainly evidence this provides the key turning point in the drama. At the end of the film Bruce Wayne trusts Selina in a way he never trusted the fire-and-violence-stoking Miranda, and fights in the daylight instead of at night. His casting off of the climbing rope can also be read a symbolic rejection of the negative emotions which consumed him in the past: no longer the terrified witness of his father’s murder, Bruce has grown to accept his father’s dying counsel to “not be afraid” and thus become a redemptive character.

Of course, the ending also seems more complex than this, for we can read the rise-from-the-pit as indicative of the negative character re-embracing fear in order to become once again an effective agent of destruction. And there is always the possibility that we are meant to read the ending in both ways at the same time, and that what Nolan is arguing is that it is the proper channeling of psychological negativity which transforms negative emotions into redemptive ones.

But regardless of how we read the “rise” from the pit, whether in the positive sense of Bruce rising over his fear (of death), or in the negative sense of “the fire rising,” the meaning of what follows is clear. As the villains Bane and Talia are killed in deaths which illustrate the inevitable consequence of their philosophy of violence, the film sweeps towards the thematically-inevitable death of Batman as well. The unexpected trick Nolan uses to make this a happy ending is pulled directly from A Tale of Two Cities, where the sacrificial death of the “wicked” Sydney Carton redeems his character while “recalling to life” his aristocratic double Charles Darney.

As in Dickens, the death of Batman in Nolan’s tale redeems the image of the caped crusader in the eyes of Gotham while “recalling to life” the benighted aristocrat Bruce Wayne. And just as the death of Batman and destruction of the wicked subconscious (note the symbolic bombing of the ocean) opens the door for the rebirth of Bruce Wayne, we see the resurrection of Gotham itself in the rebirth of the “peaceful, useful, prosperous and happy” city which has moved beyond class conflict as implied in the extended quote from the final pages of A Tale of Two Cities. The corrupt elite of Gotham’s past have been destroyed along with all of the revolutionary leaders, leaving the city and its citizens with a “clean slate” as winter transitions into spring. Wayne Manor is restored to our first image of it as a garden playground for children, closing the film with a return-to-paradise image that recalls the biblical symbolism of the trilogy’s opening scene. And while the appearance of a new Batman figure emphasizes that this mythic pattern and struggle is universal — and will continue — the privileges of wealth and power from the previous society have been erased, and the new Batman rises as a man of the people rather than a billionaire coming down from above.