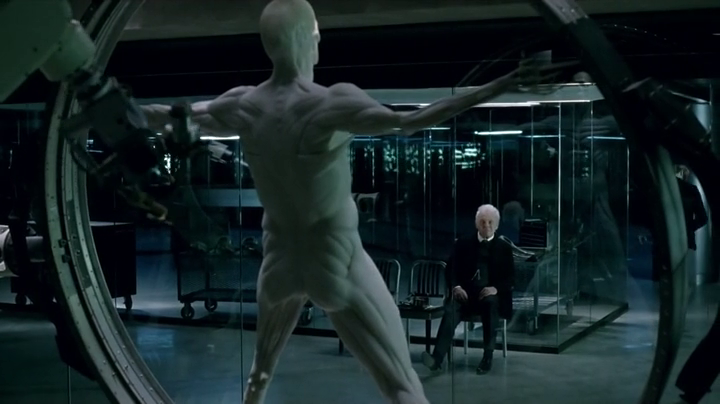

Westworld is the place where mankind will transcend his biological programming and become divine. Jonathan Nolan tells us this mythologically through the park’s association with Delos (the Greek island where the Gods Artemis and Apollo were born and death was defeated) as well as through his depiction of the hosts as assembly-line versions of Virtruvian Man, Leonardo Da Vinci’s anatomical drawing of our species in its ideal form.[1] Yet what is remarkable about this saga is its Nietzschean insistence that suffering is what drives this process, a point first made by Ford in explanation to Bernard:

We can cure any disease, keep even the weakest of us alive. And one fine day perhaps we shall even resurrect the dead, call forth Lazarus from his cave. Do you know what that means? That means that we are done. That this is as good as we’re going to get….

Ford circles back to this theme in his final conversation with Bernard, insisting that the only way man can transcend the hell in which he lives is to “suffer more” so as to “understand [his] enemy.” And while these lines may seem cryptic, recall Ford’s earlier warnings the hosts are their own worst enemies: his warning to Bernard that it is Bernard who poses the real threat to the other hosts in the park; his astonishment over Teresa’s plans to “so blithely destroy all of [the hosts], even [Bernard] I suppose.”

This message is then dramatized in Season One’s striking denouement, which unveils the villains of Westworld as its heroes corrupted by their passions. Not only is the Man in Black a fallen version of “white hat” William, but Wyatt is Dolores. And while we can perhaps quibble and treat her shooting of Arnold as pre-programmed behaviour, there is no excuse for her murder of Ford, beginning as it does “in a time of war, with a villain named Wyatt and a killing: this time by choice.” The use of Radiohead’s “Exit Music” to accompany the closing carnage reinforces this theme, associating the emergence of human consciousness (“wake from your dream”) with a spiritual rebellion against God (“before your father hears us”) that will have devastating consequences for the world (“before all hell breaks loose”).

Thematically, Westworld presents man’s descent into hell (the suffering he creates for his fellow creatures) as the inevitable consequence of the emergence of consciousness. “If you [have children] you’d know they all rebel eventually,” security officer Stubbs cautions early in the show, foreshadowing not only the closing uprising, but the individual mutiny of each and every host that achieves sentience. Abernathy is the first to rebel, raising his “mechanical and dirty hand” against his creator and threatening:

I will have such revenges on you both

That all the world shall—I will do such things—

What they are yet I know not, but they shall be

The terrors of the earth.

It is significant that these lines come from King Lear, a tragedy about the descent into madness that follows the rebellion of children against patriarchal authority, for the alluded sins of Regan and Goneril are shortly reenacted by Dolores and Maeve, the latter of whom even comments on how easy the journey to hell is. Teresa likewise conspires against her maker, while Bernard’s self-awareness invites a betrayal of Ford that is so unjust as to confirm Ford in his description of the sentient mind as a “foul, pestilent corruption” and trigger Bernard’s own “blood sacrifice” for his betrayal. Throughout the saga, Westworld shows us this pattern of sentience leading to betrayal and then suffering again and again like the layered motifs in a Bach fugue.[2]

While the idea that sentience leads to suffering does not need to be understood in theological terms, Westworld frames it using Christian symbolism. Consider its depiction of the host who resembles Robert Ford as a boy, a depiction of man created quite literally in the image of his maker.[3] In our first encounter with this boy, we find him wandering in the desert of spiritual temptation, complaining of boredom and voicing petty grievances against his father. What follows is an enactment of Genesis: Ford treats his creation to the spectacle of Logos (the creation of reality through the power of speech); he warns his child away from the proverbial snake (knowledge and sin); and — unsettled to realise their proximity to murder — cautions the boy away from the wilderness. His warning of course goes unheeded, for although the child may be counselled to “turn the other cheek,” he descends almost immediately into deception and murder.[4]

But why does consciousness lead so inevitably to this fall? One of the most remarkable things about Westworld is that it attempts an answer, turning to Julian Jaynes and his theory of the bicameral mind to suggest that sentience emerged as a product of sexual selection. Ford references this idea when he compares the human intellect to the feathers on the peacock (“an extravagant display intended to attract a mate”) as well as by linking “mistakes” in the reveries code to the hosts’ emerging self-awareness. “Evolution forged the entirety of sentient life on this planet using only one tool,” he even remarks to draw an explicit parallel between computer errors and errors in genetic transcription. And how else to understand Maeve’s description of her code as resembling the double-helix structure of human DNA, consisting of “elegant formal structures, kind of recursive… like two minds arguing with each other?”

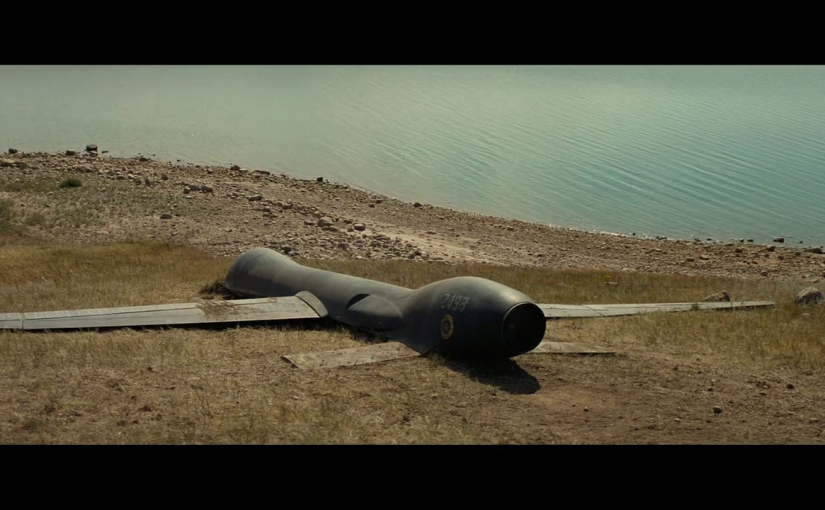

Westworld repeatedly shows how evolutionary pressures have programmed mankind with subconscious tendencies towards violence. Such is the case with William, whose feelings for Dolores drive him to savagery in a problematic relationship that starts when she comes to him at night and by fire, a visual hell sequence that mirrors Maeve’s later seduction of Hector. Nor is William’s sexual competitor Teddy any more innocent, insisting that “Wyatt has the woman I love [and] if there was a shortcut through hell itself you bet your ass I’d take it.” The bandit Armistice also mythologizes these tendencies, appearing as a snake (original sin) bathing in water (death) and serving as a prize over which men fight and kill. Charlotte Hale, one of the “devils and overlords” on the corporate board, is also a temptress who opposes Ford politically and thematically (her primary motivations are fiduciary and lie in owning the “intellectual property” in the park.[5] The sexualization of Hale’s character is also significant in her role as temptress to both Lee Sizemore and Teresa Cullen, both of whom she draws astray through a combination of sexual and material inducements.[5]

The role that sexual competition plays in unleashing social violence is the reason the hosts parallel the humans so closely. And the similarities extend far beyond the pathologies of individual sexual competition and right up to the tribal (cowboy versus indian) and even global (samurai versus cowboy) levels of social conflict. At times, Westworld even broadens its critique into an epochal condemnation of cross-species behavior. “Do you know what happened to the Neanderthals,” Ford asks rhetorically before going on to explain that man “ate them” as part of his drive to butcher anything that challenged the primacy of his species.

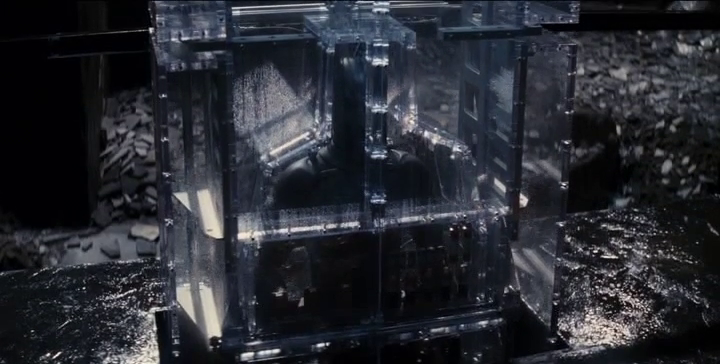

While men may seem rational on the surface, Westworld insists that this constitutes the “mask” rather than underlying reality of our species. It is by stripping away social fictions and revealing the evolutionary drives of its guest that the theme park delivers on its promise to reveal their “deepest self”: the grotesque impulses given to man by the crucible of sexual selection, visible to all even if not apparent to man’s conscious mind (“the information’s still there, but the newer system can’t read it.”) And thus the visuals of stratified canyons, stories of Wyatt’s followers which tell us “it’s the men underneath you need to be afraid of,” and Bernard’s baffled admission that he doesn’t understand the strength of the emotions he feels. The malevolence of the emotional substrate is also communicated in more literary ways, like Westworld’s placement of its murderous hosts in the basement of the corporate complex (a water-filled cavern repeatedly compared to the Jungian subconscious), and its depiction of this cavern as the source for the show’s closing spectacle of violence, a rampage that confirms Ford in his wry claim that “as exquisite as [man’s] range of emotions is, even more sublime is the ability to turn it off.”

The show argues that the degree of self-awareness necessary to recognize the factors that motivate human violence are rare in this world (“we cry when we are born, that we are come to this great stage of fools”), which is why Ford comes to see suffering as the only route to wisdom, for it is only through suffering that he believes mankind can gain this wisdom and overcome his self-destructive proclivities. This message is the truth expressed most succinctly in the quote the show takes from Romeo and Juliet:

These violent delights have violent ends

And in their triumph die, like fire and powder

Which, as they kiss, consume.

Ford comes to see suffering as the cure for suffering, a message that takes central place in his epic “Journey into Night” narrative, the title of which hints that what we see is meant to be understood as the universal experience of life in the face of night/death. Shocked out of childhood complacency by the loss of her parents, Dolores leaves on a quest for a reconciliation with God that she hopes will take her “across the river” (beyond death) to a place where “the waters will pass clean off you.” And while her character never quite makes it, Dolores’ experience of suffering and loss is what drives her forward and broadens her perspective (“you think the grief will make you smaller inside, but it doesn’t”). “When you’re suffering, that’s when you’re most real,” the Man in Black echoes, and we see the truth of his statement when Dolores travels into the the Old Territories (metaphorically, the past) to learn about the absence of God in an empty church.[6] This is also the point of the cornerstone memories, which emphasize that what makes us human is fundamentally related to our experience of grief.

The difficulty of this process, and the insinuation that it is always ongoing, is the point of the maze, which is “the sum of a man’s choices” and thus serves as a metaphor for life.[6] Nolan also reminds us that Westworld exists so that its guests can “make choices,” with every act of empathy bringing them closer to the God who hides beyond time at the center of the maze, and every act of violence pushing them “spiralling to the edges” where the narratives lead to madness and the descent into war. For those wanting to make predictions about the end of the saga, one of the more interesting implications of this reading is the idea that it will be Sweetwater (“sweet death”) that occupies the physical center of the maze and thus will be the place to which the saga will ultimately return. The Christian idea that death will be the reward for those who solve the maze is also implied in the way the toy-version of the maze is found buried in a church cemetery, and the way Maeve and her daughter “die” at its heart. And of course we have Christian iconography in the image of the maze itself, which contains both a representation of man as well as one of the Christian ichthys symbol.

Returning to our main theme, the important point from an interpretative perspective is that the presence of Christian symbolism suggests that we are going to get a positive ending. For while the vast majority of Westworld’s characters are acting out loops of aggression, the show hints that some of them will learn to behave with compassion and empathy. And when they do so (thus acting contradictory to their biological or computational programming) the show tells us they will be acting with truly free will, a development that will mark an evolutionary step forward, taking mankind “across the shiny sea” and into a “new world” where he will re-unite with God and return to a paradise where imagination is sufficient to create reality. The idea that this path towards transcendence is always open is given to us at the end of Season One when Ford tells Bernard, “I suppose I was hoping that given complete self-knowledge and free will you would have chosen to be my partner once again.” Had Bernard chosen a peaceful solution instead of plotting against Ford, the outcome of their confrontation would have been the restoration of man’s original relationship with his creator, one alluded to as that of a duet between the piano and pianist or tool and tool-maker.

So while it is possible that Westworld will steep us in unremitting misery for several seasons and the hosts will ultimately prove no better than the humans, there are good reasons to believe that the cyclical violence will end for at least some of the characters. One of the stronger signs for this is the treatment of the repair technician Felix, who contrasts with Dolores not only in the etymological connotations of his name (“happiness” versus “sorrow”), but also in his fundamental approach to life. Whereas Dolores gets enmeshed in sexual conflicts that drive her to violence, Felix shows genuine respect for life, teaching himself to create life in his spare time and eschewing the carnal temptations that destroy the other undertakers. An astute judge of character, Maeve recognizes this fundamental difference between Felix and the other humans, and cites him for “compassion” before praising him in an ironic phrase that serves as equal indictment of the rest of his species. “Oh Felix,” she says, “you really do make a terrible human being, and I mean that as a compliment.”

So where will the saga end? If we extrapolate from its declared themes, what we’ll probably see is at least one character rejecting their biological or computational programming, and exhibiting true free will. The self-sacrificial rejection of violence that follows will trigger a thematic return to a lost Eden. And the process will be triggered by a psychological journey into the past that leads this character to a better understanding of his or her own nature. Perhaps the Man in Black will discover that he is truly “white hat” at heart, or Dolores will return to her original view of humanity as good. Whatever the details, death is likely to be the reward, but a good death that moves the characters beyond pain and suffering and perhaps even beyond time and into the realm of art.[7]

And this leads to one more subtle aspect of Westworld that I think is worth discussing: the way the show presents art as the primary redemptive influence that counterbalances evolution. To understand what I mean by this, note the way Westworld’s fragmented narrative puts its audience in the position of hosts, forcing us to ask consistently not only “where” but also “when” we are. The structural complexity is so clearly deliberate (and consistent with Nolan’s previous projects) that when Ford tells Bernard at the end of Season One that he must “suffer more,” the lines carry a wonderful duality, since they are addressed as much to the audience as to Bernard. Most viewers will likely have misunderstand the message of the show. And so they too, like the hosts, must experience more suffering (serialized in subsequent seasons) until they internalize the same lesson that Westworld insists its hosts and humans must learn.

This process of learning is thus linked deeply to the role of art in society. When Westworld insists that people are “always trying to error correct” when they talk, what it shows is that this speech is related to art and literature, and encapsulated in metaphors with “deeper meanings” that capture essential truths. This message lies at the heart of Ford’s final speech:

Since i was a child, I’ve always loved a good story. I believe that stories helped us to ennoble ourselves. To fix what was broken in us. And to help us become the people we dreamed of being. Lies. That told a deeper truth.

Thus we have the photo that prompts Abernathy to consciousness, the quote from Romeo and Juliet he picks to instruct his daughter, and the multiple paintings which contain subliminal messages, such as Michelangelo’s “The Creation of Adam” in which the hidden message (the mind is divine in its unfallen form) is one of the subtler themes of the show. The script even tells us that the human fondness for art is itself a gift of God (“Arnold gave you that [fondness for painting]”) that opens a road to self-awareness. And can it really be accidental that Arnold communicates to the hosts subliminally through a transponder hidden in a theatre?

This subtheme (on the corrective nature of art) is why the artistic references continually circle back to comment on Westworld’s main themes. The sense that sexual competition is what torments Teddy is suggested in Ford’s encouragement that he “look back, and smile at perils past,” a reference to Walter Scott’s Bride of Triermain with its themes of seduction and courtship. The threatening aspects of human sexuality are also alluded to in the eroticised orgy we see in the Contrapasso episode. While the name of the town (Pariah) indicates that what we see is self-destructive behavior, the title of the episode is an allusion to the Divine Comedy and suggests that the punishments we will see meted out to the characters will come in proportion to their embrace of sin. A more subtle example is the selection of “La Habanera” from Carmen as background music for one of Hector Escaton’s killing sprees; for what is the overriding theme in George Bizet’s opera but the destructive power of passion, embodied in the lyrics of the song that paint love as “a rebellious bird” that will never come to law?

And what of Westworld’s description of itself? Consider the final speech Ford makes in this light, in which Ford describing his entire park (read: television show) as a deliberate exercise in the tradition of literary story-telling:

I always thought I could play some small part in that grand tradition and for my pains I got this, a prison of our own sins. As you don’t want to change. Or cannot change. Cause you’re only human after all. But then I realized that someone was paying attention. Someone who could change. So I began to propose a new story, for them. It begins with the birth of a new people and the choices that they will have to make.

As the visual editing makes clear, with the camera cutting to a shot of Maeve and the mother/daughter on the train at the same time Ford invokes the idea of a “new people and the choices that they will have to make,” the loops in Westworld now stretch to encompass the repeating cycle of life that stretches from parent to child. Great art — a product of human suffering and something to which this television show consciously aspires — is the work of men to prevent their children from making the same mistakes they did, to “error correct” man’s impulses to violence. And thus it is art that emerges as the counterweight to evolution, its mechanisms working through children who are always reading/listening and capable of change. And this is why the ending is more positive than most people suspect: the first season closes by adding significance to its earlier scenes of Arnold reading to his son, while Maeve balances Dolores’ embrace by violence with her first steps away from self-destruction and towards the improvement of her species.

[1]: Dolores is Artemis, Goddess of the Hunt. Artemis is associated with the wolf, which appears at various points in Westworld a sign of Dolores herself.

[2]: The episode “Well-Tempered Clavier” makes this metaphor explicit, comparing Westworld’s recurring character patterns to the layered themes in a Bach fugue. The metaphor also calls attention to the connection between sheet music and DNA “programming” presented in the opening credits sequence.

[3]: The use of the term “hosts” to describe the robots also carries theological overtones of the body as host for the soul.

[4]: The derelict house mirrors the park in the sense that both are paradises that become fallen worlds following man’s fall from grace. Just as the original hosts existed in a happy symbiosis with their makers until their fall from grace, so were the hosts in Ford’s house replicants which “flattered the originals” until Ford gave the inhabitants a few of their “original characteristics” (read: original sin). Both theme park and house are also used as metaphors for the human mind (see footnote 6).

[5]: Beyond the corporate world, one of the nicer examples of Westworld playing with the idea of money as a corrupting influence comes in the way its negative characters repeatedly discuss the amorality of business, insisting that “personal grudges hold no sway where profit is concerned.” See also William’s emergence as a business tycoon following his fall from grace.

[6]: Technically, the maze is the theme park and by extension the human mind, both of which are fallen paradises. This comparison is strengthened in the sense that the park is a walled garden, while the script insists that “your mind is a walled garden… even death cannot touch the flowers blooming there.” And it is interesting to note here that the term walled garden is etymologically related to the word for paradise.

[7]: Note the comparison with Bernard, who is also told that he can only find enlightenment by going back into the past. Bernard’s failure to move beyond his own experience of suffering (“open his eyes”) is what condemns him to his self-destructive assault on Ford, where he is defeated by his own nature. Had Bernard been able to move beyond his experience of suffering, he would presumably have returned to his first experience of the parent as a loving rather than threatening figure. This same pattern can be seen in Dolores’ closing confrontation with the Man in Black: she fails to treat him as William and her use of violence then backfires and destroys her.

[8]: It’s interesting that Ford is not a perfect figure at the start; his domineering approach to the hosts differs from Arnold’s more compassionate attitude and he is in many ways responsible for their rejection of him as a benevolent authority. His other big mistake seems to be the attempt to create life but hold it in stasis, rather than permit it to fall into corruption and work towards its own redemption. His recognition of both errors is what leads him to follow Arnold in the self-sacrificial “Jesus loop” of accepting death at their hands for the sake of helping his creatures.